My Air Raid Response Protocols

anelson August 31, 2024 #ukraine #kyiv #air raidIn a previous post I made mention of the air raid alarms that we have all become accustomed to hearing in Ukrainian cities almost daily. This post expands on that topic, describing how I gauge the risk of and air raid and how I respond based on that risk. This is just my own opinion, trying to make do in a difficult situation as best that I can. My colleagues and friends in Ukraine all have different approaches to this threat.

Immediate Response to Air Raid Alarm

I find out about an air raid in one of two ways (sometimes both simultaneously): an alert on my phone from the Digital Kyiv mobile app, or the sound of the air raid sirens on the street outside.

At this point in the war, in central Kyiv at least, the air raid alarm can be caused by a wide range of signals, which vary in specificity and risk. So, my first step is to try to understand why this signal has been triggered.

To my knowledge, there aren’t real-time official government sources for this information (if you’re aware of something, get in touch!). There are, however, a number of Telegram channels that I look to for information. A few if you’re curious are:

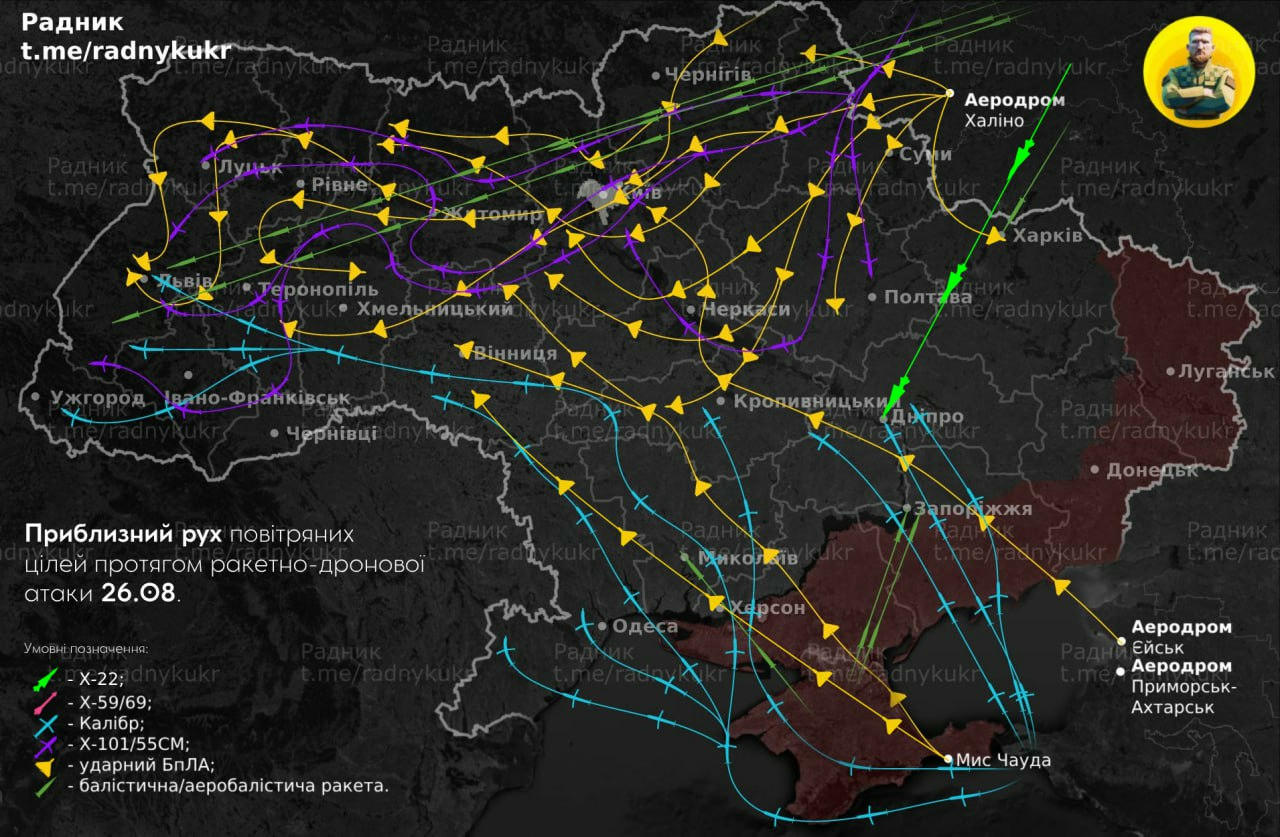

- Радник (“Radnik”)

- @war_monitor

- @insiderUKR

By the time the air raid alarm sirens are audible, there’s usually something in one of these channels as to why. If not, I can usually find something within a minute or two of the alert.

The key is to determine what is causing the alert, because that determines my reaction to the threat.

I evaluate this based on two factors:

- What kind of threat is it?

- How specific is it?

I’ll share some examples below.

Russian Military Aviation Taking Off

Often when Ukrainian air defense radar detects Russian combat aircraft taking off from Russian air bases, if those aircraft are capable of carrying air-launched missiles that can threaten Ukraine, an air raid alert will be triggered for a large part of the country, just in case. Ukrainian defenders can’t know immediately if the aircraft is on a combat mission, or if so what the target is, so if there’s a potential threat they trigger the alarm.

If I see this is the reason for the alert, I take no action. I consider the risk to be minimal, and not worth the disruption.

Ballistic Missile Launch (Generic)

This indicates a ballistic missile was detected (in this case from the North but they can come from the East or from Crimea in the South). This is usually a very broad alert as well, because ballistic missiles move very fast there’s not much warning, so the alert can apply to the whole country or several oblasts.

This gets my attention, and makes me more wary. If possible I’ll try not to stand next to an exterior window, and if I’m out walking I may switch to the underground passageways if I’m in an area that has them. But I don’t consider it a big risk.

Ballistic Missile Launch (Specific)

This gets more attention. The threat is specifically to the Kyiv region. My response is the same as a generic ballistic missile alert, but I am more nervous.

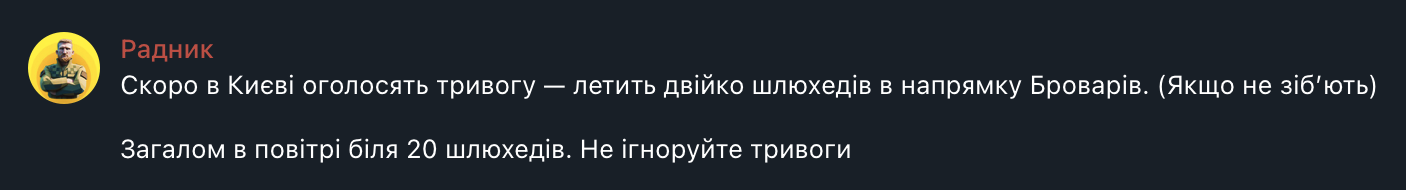

Multiple Shahed Drones in Kyiv

This I consider to be a more dangerous situation. Particularly if it’s a large number of kamikaze drones. The AFU air defenses are particularly good at shooting these down, but even when shot down they still have to land somewhere, and sometimes their warhead hasn’t detonated before they hit the ground. The risk of falling debris from a successful interception by air defense exists for the ballistic missile scenarios as well, but given the larger number of drones the odds that some debris will hit me go up. This is just the math of the situation. Shaheds are also much cheaper than ballistic or cruise missiles, so Russia fields more of them.

In this case I will make sure I’m not close to any windows, I’ll close any windows that are cracked (of course explosives can blow out the window when it’s closed, but it will take more force to blow out a closed window than one that’s cracked), and may move to a position in the apartment where there are thick brick walls between me and the outside. A direct hit from above is probably game-over no matter what, but lateral impacts could be survivable if one is shielded from the blast and not sheltering directly at the point of impact.

On a somewhat humorous note, the Iranian bastards who sell these drones to Putin call them “Shahed”, which I think is the term in Islam for a holy warrior who martyrs himself. However, when writing messages about drone threats, Radnik calls them “шлюхеді” (pronouned “shlyuhedy”), which is a portmanteau of an offensive Ukrainian word for a promiscuous woman, and “Shahedi” (plural form of “Shahed”). It makes me smile every time I read those alerts; the juvenile vulgarity is funny when juxtaposed with the seriousness of the topic.

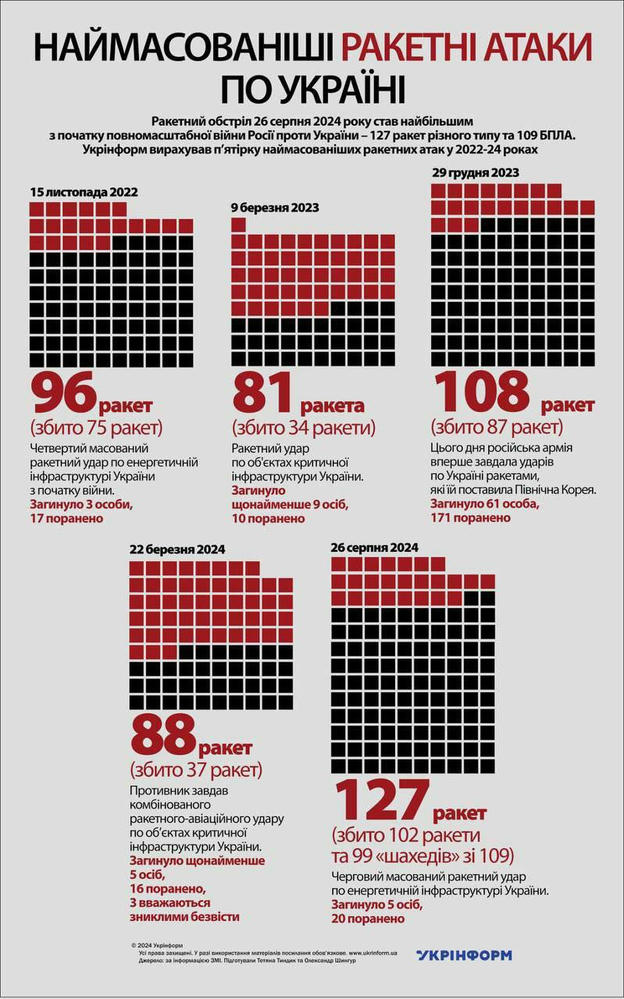

Mass Attack

I can’t tell you what I would do if I saw this, because I found out about this mass attack when I woke up to the sounds of explosions, either from AFU air defense batteries or from Russian cruise and ballistic missile impacts. I like to think I’d go to the shelter proactively.

Mitigating Factors

One of my rules is that if I hear explosions, either air defense batteries firing or ordnance landing, I go to the shelter. My thinking here is that when something has already kicked off close enough that I can hear it, the odds of additional impacts dramatically increase, as does the risk. I’ll talk more about the protocol for bugging out to the shelter a bit later.

A mitigating factor in the other direction is sleep. While it’s possible to configure the Digital Kyiv app to play a loud alarm sound when there’s an air raid alarm, regardless of the time of day or night, I turned that off after a couple of days here. It’s simply unbearable. It’s not possible to get a normal night’s sleep, and in most cases the cause of the alarms are such that my standard protocol is to take no immediate action anyway. It happens that most Russian attacks are in the early morning, between 4AM and maybe 7AM, so it happens often that I ignore air alarms by virtue of being asleep, and discover the threat when I awake to the sound of an explosion.

Bugging Out

If I hear an explosion, it’s time to go to the shelter. It’s a simple rule, that can be evaluated even when one is groggy from just waking up. When this happens my brain tries to negotiate it’s way out of this. It thinks “maybe that was just a car back-firing. it wasn’t very loud. it sounded far away.” If I’m very tired I sometimes let it get away with this, until I hear another explosion that is undeniably an explosion. But in any case, at some point, booms == bug out.

I have a pre-arranged plan for how this works. My wife’s and my bug-out bags (remember from a prior post, Ukrainians call these “alarm suitcases”) are next to the door, as are a pair of 5.11 pants, socks, and a shirt. I jump out of bed, grab my phone and laptop, stow my laptop in a dedicated pocket in my bug-out back, put on my 5.11 pants, shirt, and socks, then boots and an ankle-mounted tourniquet. We leave the apartment, lock the door, and make haste down the stairs (I live on the 6th floor of an apartment building with no elevator), and across the street to the nearest Metro station.

During this process I always feel silly, because inevitably there will be people out on the street not reacting at all. I feel like I’m the one chicken-shit who can’t handle a little bit of exploding Russian ordnance, and feel ashamed. But then I get into the metro and it’s packed w/ people taking shelter, and I don’t feel so stupid after all. It’s a bizarre psychological quirk. It happens every time.

Sheltering

Once I arrive in the shelter, I feel a sense of relief. This metro station is deep underground, dug specifically to provide shelter against NATO nukes in the event that WW3 kicked off in the Ukrainian SSR.

I was not in Kyiv in the early days of the war, when people were living in metro stations for days on end under relentless Russian barrage. I presume it was terrifying then. But now, the mood in the metro during an air raid is probably not what you’d expect. It’s quite casual. If you didn’t know the context, you’d think it’s just a bunch of Ukrainians waiting their turn at the DMV to renew their driver’s licenses, only for some reason doing it in a metro station.

Having done this a few times now, I carry some preps to make it more comfortable. I may do a separate post about the actual contents of my bug-out bag, but for now I’ll say that I have a packable camp chair that I deploy and can relax in comfort as I wait for the threat to pass.

As you can see in the photo, many Kyivans have the same idea. There are also some very compact folding camp stools that were donated to Ukraine from somewhere, that they pass out during air raids for people who don’t have their own chairs. I sat on one of those during my first air raid, and ordered my wife and I camp chairs while we were still underground.

All-Clear

When I see the all-clear signal for an air raid that I didn’t do anything to respond to, it’s a kind of smug relief. Something like “ha, I rolled the dice and won! it wasn’t anything to worry about!”.

When I get that message from inside the shelter, it’s a different kind of relief, like the recess bell ringing at school. Typically I’ll be in the shelter for 30 minutes to a few hours, and it gets very dull. Especially since these air raids almost always happen when I’m asleep, so I’m tired and groggy and not in any mood to doom-scroll or get some work done. Everyone generally gets it all at once, and there’s a mass exodus out of the shelter. It takes me a couple of minutes to pack up my fancy camp chair, so I’m usually one of the last ones out.

I have never emerged from the shelter nervous about what I might find, worried that maybe my apartment building was hit and all of my stuff is scattered across the courtyard in a smouldering mess. Mainly because I think I would notice it even from underground. In my bed, I can feel the rumbling in the ground when a train goes through the metro 100s of feet below me; I’m fairly sure a Russian warhead exploding where my bed is would be noticeable from inside the metro station as well. In fact, I always emerge strangely carefree, as if the threat is definitely passed, there’s nothing to worry about, we survived, now let’s get on with our day.

Often the wife and I will get breakfast afterward, if restaurants are open yet.

Aftermath

You might imagine that this whole life-and-death experience is psychologically draining, and maybe leaves some emotional scars. But it’s not like that. It’s…mundane. It’s an annoyance, like having to wait a long time for a bus. The worst part is the sleep disruption, since as I’ve noted these attacks usually happen in the early hours of the morning. I know I’ll be mostly useless the whole day due to the sleep deprivation. I can’t complain about this to my Ukrainian colleagues since they obviously live through it (although most of them just stay in bed and try to ignore the explosions), and I can’t complain about it to my American colleagues because they wouldn’t understand and I don’t want to alarm people unnecessarily.

I almost never find out details about what happened in the air raid. Were those explosions Ukrainian air defense batteries, or Russian ordnance blown up mid-air, or a successful hit on a Russian objective? Where were the explosions relative to me? What was the damage? This is intentional, and in fact it’s illegal to post information on social media that would help the Russian forces perform a post-attack BDA (Battle Damage Assessment).

However, sometimes you know. In the case of the Monday attack, it was widely publicized.

Strangely, after surviving one of these attacks I feel some sense of accomplishment. I didn’t do anything, I didn’t help shoot down any Shaheds or rescue any elderly from a bombed-out building or even find someone’s lost cat in the shelter. But nonetheless there is a feeling that my mettle was tested and I passed somehow. War does strange things to the mind.